How Termination Conditions Strengthen Agentic Systems in R&D

In practice, termination is a function of coverage saturation, diminishing returns, decision risk, and the artifacts required for the task.

.png)

Any researcher who has submitted a paper to a journal for publication understands termination conditions. The author writes the manuscript, reviewers send back critiques, revisions follow, and at some point, the editor decides the paper is “good enough” for publication. That decision is not arbitrary. It reflects implicit thresholds on evidence completeness, methodological clarity, limitations, and residual risk.

Termination conditions are predefined criteria that specify when an AI agent’s task is considered complete or when it must stop.

Agentic research systems face the same problem. Once you have solved retrieval and built scientific-grade reasoning, a new question appears: how do multi-agent systems stay on task, avoid drift, and decide when an answer is sufficient for the purpose it serves?

This is precisely the orchestration problem. Search and Retrieval determine what the system can see. Reasoning determines how it interprets that evidence. Orchestration determines whether multiple agents can run this process end-to-end in a controllable way and stop at the right depth. In R&D, the required depth ranges from quick desk research to outputs that resemble a systematic evidence review.

Why termination conditions matter

Scientific questions are open-ended. There is always one more trial, one more registry analysis, and one more subgroup to check. In that environment, simplistic rules like “run N steps” or “stop when the model is confident” are unreliable.

For an R&D organization, termination conditions matter for three reasons:

- Scientific quality – The bar for a target ideation exercise is lower than for a survival analysis that informs a protocol or a governance pack. Termination needs to reflect the risk profile of the decision, not just model confidence.

- Cost and latency – Infinite exploration is expensive. The system must recognize when additional retrieval is unlikely to change the conclusion.

- Trust and governance – Reviewers need to see why the system stopped where it did, and which gaps remain. Without that transparency, even a strong answer will not pass internal QA.

In practice, termination is a function of coverage saturation, diminishing returns, decision risk, and the artifacts required for the task (evidence tables, assumptions, limitations, provenance). Those criteria are exactly how a good principal investigator decides that a review is ready for a meeting.

How humans orchestrate research today

The journal analogy is useful because it illustrates orchestration as a dialogue.

- The author proposes a synthesis of the evidence.

- The reviewers stress-test it: they ask for missing analyses, challenge assumptions, and insist on clearer limitations.

- The editor decides when the paper has crossed the bar for publication.

Pharma and biotech teams reproduce the same pattern internally. A scientist drafts a review; peers and governance boards critique it; revisions go back and forth until everyone agrees the evidence is sufficient to make a decision.

In other words, we already operate with termination conditions in human scientific workflows. They are encoded in SOPs, templates, and tacit norms about what is acceptable in discovery reviews, safety assessments, or epidemiology summaries.

The goal in agentic systems is to make this logic explicit and machine-operational.

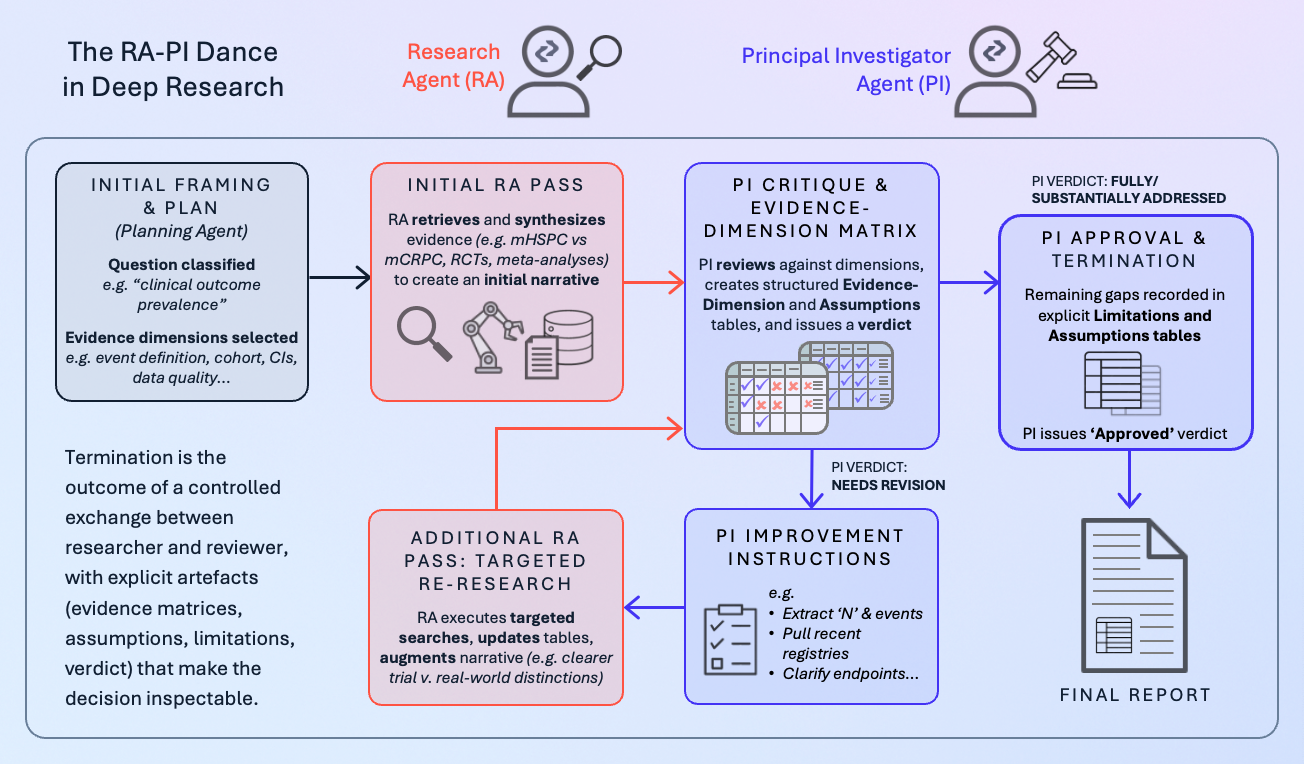

The RA–PI dance in Deep Research

In the Causaly Agentic Research Suite, Deep Research is the modality that runs long-form, plan–execute investigations with provenance and auditability. Underneath, it relies on a structured interaction between a Research Agent (RA) and a Principal Investigator Agent (PI), supported by retrieval and planning components.

You can see this in the example of a Deep Research report in Causaly on metastatic prostate cancer survival. Before the executive summary, the report exposes the thinking path: how the system framed the question, which evidence dimensions it decided to use, how retrieval was executed, and how the PI evaluated the initial synthesis.

The interaction follows a pattern that closely mirrors author–reviewer dynamics:

- Initial framing and plan: The system classifies the question (“clinical-outcome prevalence” for PFS/OS in metastatic prostate cancer) and selects relevant evidence dimensions: event definition, cohort, numerator/denominator, incidence with confidence intervals, and data source quality.

- First RA pass: The Research Agent retrieves and synthesizes evidence: distinguishes mHSPC from mCRPC, surfaces RCTs, meta-analyses, and registries, and produces an initial narrative.

- PI critique and evidence-dimension matrix: The Principal Investigator Agent reviews this synthesis against each evidence dimension. In the example, it flags missing sample sizes and event counts, inconsistent confidence intervals, shallow data-source quality appraisal, and over-aggregation across heterogeneous trials. These points are captured in a structured evidence-dimension table and an assumptions table, not just in prose.

- Improvement instructions and “needs revision” verdict: Rather than vaguely asking for “better quality,” the PI issues concrete improvement instructions: extract N values and event counts for key studies, retrieve CIs or compute them, pull recent registries, stratify by treatment era and regimen, and clarify endpoint definitions. The run is explicitly marked “needs revision,” delaying termination.

- Targeted re-research and second RA pass: The RA executes these targeted searches, updates tables with N, events, CIs, and hazard ratios, and augments the narrative with clearer distinctions between trial and real-world cohorts.

- Final PI verdict, limitations, and assumptions: The PI re-evaluates the evidence dimensions. In the example, all core dimensions move to “fully addressed” or “substantially addressed,” with remaining gaps recorded in a limitations table and an explicit assumptions table (e.g., residual heterogeneity in PFS definitions, limits of registry data). The PI now issues an “approved” verdict. Only then does the system present the executive summary and main report to the user.

Termination here is not a magic threshold inside a single model. It is the outcome of a controlled exchange between a research role and a reviewer role, with explicit artifacts (evidence matrices, assumptions, limitations, verdict) that make the decision inspectable.

Why “good enough” depends on the question

A key point for orchestration is that “good enough” is not a universal standard. It depends on what the user is trying to achieve.

- For exploratory desk research, the PI can accept partial coverage on some dimensions if the goal is orientation and hypothesis generation. Termination conditions emphasize breadth and speed over exhaustiveness.

- For systematic-style evidence packs that inform protocols or governance, the same PI agent should push the RA deeper: more loops, stricter thresholds on confidence intervals and study characterization, and a fuller limitations and assumptions table.

In the Deep Research report example, you see this gradient explicitly. The first PI review accepts that the narrative is directionally correct but rejects it as incomplete for decision use, triggering another cycle. The second review accepts residual limitations as “largely unavoidable with published sources” and approves the synthesis with clearly documented constraints.

From an orchestration perspective, this is a delicate dance. If the PI is too strict for low-stakes questions, the system feels slow and overengineered. If it is too lenient for high-stakes questions, the outputs will not survive scrutiny. The termination logic has to encode both the purpose of the question and the evidence standards of the organization.

Avoiding drift without over-constraining agents

Multi-agent systems are prone to drift and scope creep once they are allowed to call each other freely. A research agent can easily follow interesting but irrelevant paths; a reviewer agent can keep asking for refinements that never converge.

The RA–PI loop keeps this in check by narrowing communication to structured objects:

- A shared representation of the question and evidence dimensions.

- Tabular assessments of coverage and assumptions.

- Improvement instructions that are specific and finite, not open-ended.

Because both RA and PI operate against the same ontology of evidence dimensions and the same study schema, they stay aligned on what “progress” means. And because the run carries a manifest of all actions and verdicts, scientists can replay the path from initial framing to approved report.

What senior leaders should look for

For CIOs, Heads of R&D IT, and senior scientific leaders, the orchestration question becomes practical when you look at real outputs rather than architectures.

When you evaluate a system that claims to do “deep research” or “agentic reasoning,” check whether you can see:

- A visible thinking path before the executive summary: how the question was framed, how evidence dimensions were chosen, and which searches were run.

- A Research–Reviewer interaction that looks like an internalized peer-review loop, including explicit verdicts such as “needs revision” and “approved.”

- Evidence-dimension, limitations, and assumptions tables as first-class artifacts, rather than afterthoughts.

- Termination conditions that clearly depend on the task type and risk profile, rather than opaque step limits or generic confidence signals.

Agentic AI in R&D will only be trusted when it mirrors the discipline of human scientific review. Retrieval and reasoning are necessary foundations, but they are not sufficient. The systems that will matter most are those that encode a clear RA–PI dance, expose their own review cycle, and make termination a transparent decision that scientists can understand, critique, and ultimately rely on.

Further reading

Get to know Causaly

What would you ask the team behind life sciences’ most advanced AI? Request a demo and get to know Causaly.

Request a demo.png)

.png)

.png)

%20(14).png)

.png)

%20(5).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)